How to Adapt Scrum for Hardware: A Project Manager’s Guide to Physical Product Agility

In summary:

- Stop forcing software sprints onto hardware; instead, analyze your product’s “layers of changeability” from firmware to tooling.

- Redefine “Done” for hardware teams: the output of a sprint is often a “Knowledge Asset” (like a simulation), not just a functional feature.

- Shift testing left by embracing digital twins and Hardware-in-the-Loop (HIL) simulation to drastically reduce physical prototyping cycles.

- Align budget ownership with decision-making power by distributing financial responsibility across roles (Product Owner, Engineering Manager).

As a Project Manager steeped in software development, you’ve witnessed Scrum transform chaotic projects into models of efficiency. You live and breathe sprints, standups, and retrospectives. Now, tasked with a hardware project, you’re trying to apply the same playbook, but it feels like forcing a square peg into a round hole. The common advice—”hardware is different,” “use longer sprints”—is frustratingly vague and misses the point. The physical constraints of manufacturing, tooling, and supply chains seem fundamentally at odds with the fluid nature of Agile.

The friction isn’t imaginary. Trying to manage atoms with a process designed for bits leads to “Agile theater,” where teams perform the rituals of Scrum without reaping any of the benefits of speed or flexibility. They hold standups about parts stuck in customs and conduct retrospectives that devolve into complaints about physics. This approach doesn’t just fail; it often makes teams slower and more frustrated than they were under a traditional Waterfall model.

But what if the problem isn’t Scrum, but our interpretation of it? The key to unlocking agility in hardware isn’t to abandon Scrum’s principles, but to translate them. The secret lies in deconstructing your physical product into a spectrum of changeability—from easily modified firmware to costly and immutable tooling. By understanding the true “cost of change” at each layer, you can apply targeted Agile tactics that work with physical constraints, not against them.

This guide will provide a new mental model for adapting Scrum to the physical world. We will move beyond the platitudes and explore the specific translations, frameworks, and mindset shifts required to deliver complex hardware with genuine speed and flexibility. We will deconstruct common Scrum rituals and rebuild them for the unique challenges of hardware development, turning your software expertise into a powerful asset in the world of physical products.

Summary: How to Adapt Scrum for Hardware: A Project Manager’s Guide to Physical Product Agility

- Why Waterfall Deadlines Clash With Scrum Flexibility in Manufacturing?

- How to Run a 15-Minute Standup That Actually Solves Blockers?

- Scrum Master or Project Manager: Who Owns the Budget?

- The Ritual Mistake That Makes Agile Teams Slower Than Before

- When to Reject New Feature Requests During an Active Sprint?

- When to Choose Low-Code Robotics Platforms for In-House Tweaking?

- Canary Release or Blue-Green Deployment: Which Is Safer?

- How to Implement Rapid DevOps Cycles Without Crashing Production?

Why Waterfall Deadlines Clash With Scrum Flexibility in Manufacturing?

In software, a deadline is a target for a set of features. In manufacturing, a deadline often represents an irreversible commitment to high-cost tooling and production lines. This fundamental difference is where many Agile hardware initiatives fail. A Waterfall-style, date-driven deadline forces teams to lock in designs prematurely, accumulating massive technical debt before the first unit is even produced. The clash isn’t about having a deadline; it’s about what that deadline represents. For Scrum to work, the “deadline” must be for delivering value and learning, not for locking in a physically unchangeable design.

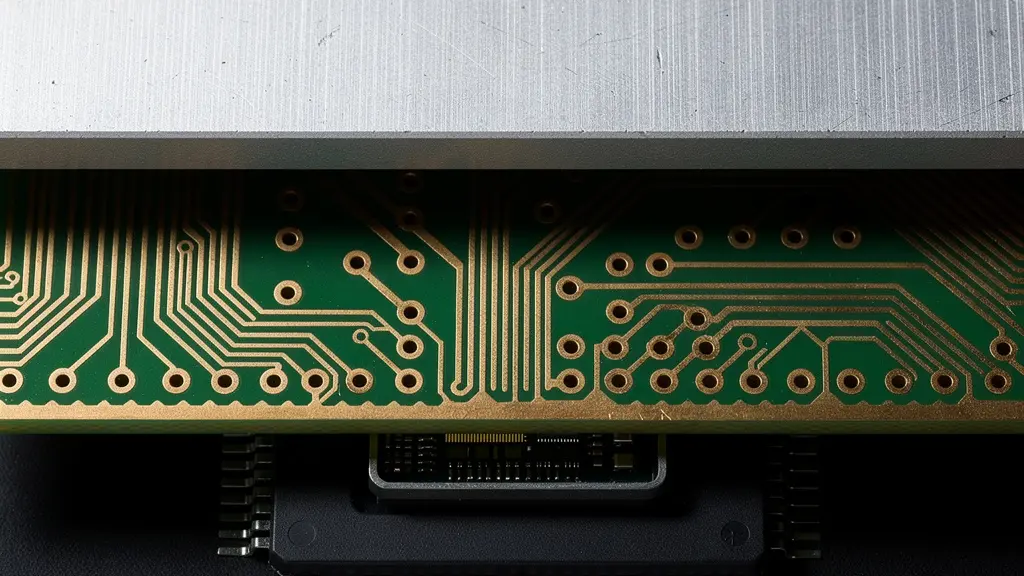

The solution is to replace rigid, all-or-nothing gates with a flexible, modular architecture. Instead of one massive design review, you establish clear “exit criteria” for different phases. For example, a sprint goal might be to validate the interfaces between a new sensor and the main PCB, not to finalize the entire enclosure design. This approach allows the design to remain fluid where the cost of change is low (firmware, PCB layout) while progressively solidifying elements with high-cost implications (injection mold tooling, custom silicon).

This mindset treats the product not as a single entity, but as a system of modules with independent development cadences. By building and testing “stubs” of each module early on, you de-risk the integration points—often the biggest source of delays and cost overruns. This transforms the development process from a high-stakes gamble on a single “big-bang” integration to a series of smaller, manageable bets. You’re not eliminating deadlines; you’re making them smarter and aligning them with the physical and financial realities of manufacturing.

How to Run a 15-Minute Standup That Actually Solves Blockers?

The classic “three questions” standup often falls flat in hardware teams. Reporting on what you did, what you’ll do, and your blockers becomes a status update for the manager, not a problem-solving session for the team. The most significant blocker might be a delayed component shipment or a physics problem that can’t be solved by talking. A truly effective hardware standup must shift its focus from reporting status to unblocking physical progress. This means the meeting’s center of gravity shouldn’t be a whiteboard, but the product itself.

Gather the team around the physical prototype on the test bench, the CAD model on a large screen, or the digital twin simulation. Instead of abstract discussion, team members can point to the specific component causing an issue, manipulate the 3D model to show an interference, or review the latest simulation results together. This physical context makes problems tangible and facilitates immediate, collaborative brainstorming. The goal is to leave the standup not just with an updated list of blockers, but with concrete next steps or experiments to run that day to solve them.

This approach emphasizes rapid feedback loops, a concept brilliantly demonstrated by Hitachi Energy. For their RoadPak project, they needed to get feedback from Formula E racing teams. Instead of waiting for a finished product, they created a specialized “evaluation kit.” As described in a case study on their agile hardware development, this kit allowed customers to test core components in their own environments. This short-circuited the feedback loop, turning theoretical blockers into practical, solvable problems and dramatically accelerating development by focusing on tangible, testable value.

Scrum Master or Project Manager: Who Owns the Budget?

In a traditional project, the Project Manager “owns” the budget. Applying this model to hardware Scrum is a recipe for conflict and bottlenecks. A Scrum Master’s role is to facilitate the process, not control finances, while a Product Owner is focused on maximizing value, not managing capital expenditure. The question itself is flawed because it assumes a single owner. In an effective Agile hardware organization, budget ownership is distributed and aligned with decision-making authority.

No single person owns the entire budget. Instead, different leaders are responsible for different *types* of financial decisions, reflecting the different “layers” of the project. The Product Owner controls the “Value Budget,” making trade-offs on feature prioritization to maximize ROI. The Hardware Engineering Manager oversees the “Platform & Tooling Budget,” managing long-lead items, lab equipment, and Non-Recurring Engineering (NRE) costs. The Project Manager, in this adapted role, might manage the overall “NRE Runway,” ensuring long-term capital efficiency, while the Scrum Master champions “Budget Transparency,” making sure the team has real-time visibility into costs like the Bill of Materials (BOM).

This distributed model prevents a single person from becoming a bottleneck and empowers teams to make informed decisions within their domain. A clear framework is essential for this to work without creating chaos. The following matrix illustrates how these responsibilities can be defined.

| Role | Budget Responsibility | Decision Scope | Key Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Product Owner | Value Budget | Feature prioritization and value delivery | ROI per feature, customer value metrics |

| Hardware Engineering Manager | Platform & Tooling Budget | NRE costs, lab equipment, long-lead items | NRE utilization rate, equipment ROI |

| Scrum Master | Budget Transparency | Cost visibility and tracking | BOM cost variance, sprint budget burn rate |

| Project Manager | NRE Runway | Long-term capital allocation | Capital efficiency, milestone achievement |

By defining these roles and responsibilities, as detailed in the Scrum in Hardware guide, the organization aligns financial control with the people best equipped to make specific trade-offs. This fosters a culture of fiscal responsibility at all levels and enables the team to move faster by making localized, data-driven financial decisions.

The Ritual Mistake That Makes Agile Teams Slower Than Before

The single most damaging mistake in hardware Scrum is “cargo culting”—mindlessly performing software rituals without understanding their underlying purpose. The worst offender is often the retrospective. A software team’s retro might focus on improving communication or process. For a hardware team, this can feel abstract and unproductive. The real obstacles are often rooted in physics, materials, and manufacturing constraints. The ritual mistake is holding a process-focused retro when the team needs a physics-focused learning cycle.

An effective hardware retrospective should be a “Design-Build-Test-Learn” (DBTL) review. The questions aren’t “What went well?” but “What did the simulation predict? What did the physical test reveal? Why was there a variance? How does this new knowledge update our model?” The output isn’t a process improvement; it’s a Knowledge Asset—an updated simulation model, a material characterization report, or a validated failure analysis. This transforms the retro from a therapy session into a critical, value-generating engineering activity.

Case Study: WIKISPEED’s Test-Driven Hardware Development

Team WIKISPEED provides a powerful example of this principle in action. Instead of relying on expensive and slow physical crash tests, they embraced Test-Driven Development (TDD) for hardware. As highlighted by their approach at Scrum Inc., they used data from an initial physical test to build a computer simulation that could accurately replicate crash events. From that point on, they “crash tested” their designs virtually within each sprint, iterating and improving at a fraction of the cost and time. A physical test was only used for final validation after many cycles of virtual learning, saving millions of dollars and dramatically accelerating their time-to-market.

This focus on tangible learning over abstract process is the key to avoiding Agile theater. It requires a fundamental shift in how the team perceives sprint goals and “done” work, moving from a feature factory to a knowledge factory.

Action Plan: Avoiding Common Hardware Scrum Pitfalls

- Review Cycles: Replace software-style retrospectives with ‘Design-Build-Test-Learn’ cycle reviews focused on physics and performance.

- Spike Outcomes: Mandate that hardware spikes result in concrete ‘Knowledge Assets’ like characterization reports or simulation models, not just opinions.

- Backlog Structure: Implement hierarchical backlogs, breaking a top-level feature backlog into discipline-specific backlogs (Mechanical, Electrical, Firmware).

- Definition of Done: Create an iterative Definition of Done that evolves with product maturity rather than using a universal, static one.

- Team Organization: Break down hardware development into smaller sub-teams working on specific product aspects to enable parallel progress.

When to Reject New Feature Requests During an Active Sprint?

In software, accommodating a new feature request mid-sprint is sometimes possible with clever refactoring. In hardware, a seemingly small request can have colossal ripple effects, potentially invalidating months of work and millions in tooling investment. The decision of when to reject a request isn’t about the team’s capacity; it’s a stark economic calculation based on one core concept: the Cost of Change Spectrum.

Every hardware product exists on this spectrum. At one end, you have firmware—infinitely malleable and cheap to change, just like software. In the middle, you have the PCB layout; changes are possible but require a new board spin, costing time and money. At the far end, you have things like injection mold tooling or a custom ASIC design; once committed, changes are prohibitively expensive or outright impossible. A Project Manager’s primary role in a hardware Scrum team is to be the guardian of this economic reality. You must protect the sprint from changes that fall on the high-cost end of the spectrum.

The rule is simple: the decision to accept a change is inversely proportional to its cost. A request to change a UI color in the firmware? Discuss it with the Product Owner. A request to move a mounting hole by 2mm after the injection mold is cut? The answer is a firm, immediate “no,” deferred to a future product generation. This ruthless prioritization is what enables speed. In fact, R&D shops that master this discipline produce quality prototypes up to eight times faster than their Waterfall counterparts. They aren’t faster because they work harder; they’re faster because they don’t invalidate past work with high-cost changes.

When to Choose Low-Code Robotics Platforms for In-House Tweaking?

The “Cost of Change Spectrum” presents a major challenge: how do you get user feedback on interaction logic when the custom hardware is months away from being ready? Waiting for the final product is a Waterfall trap. This is where low-code and off-the-shelf robotics platforms become a strategic tool for de-risking the user experience and control logic in parallel with core engineering.

These platforms (like Viam) or even advanced simulators allow you to build “sacrificial prototypes” that mimic the intended user interaction. They let you test hypotheses about usability, control algorithms, and system logic using readily available components. This is invaluable for separating the development of the high-cost physical components from the more malleable software and firmware layers. While the mechanical team is designing the custom chassis and the electrical team is laying out the PCB, the systems team can be testing 80% of the firmware code against the low-code platform’s APIs.

The primary use case for these platforms is not to build the final product, but to accelerate learning and validate assumptions. They enable non-engineers, like Product Managers and UX designers, to independently build and test concepts, gathering real user feedback in days instead of months. This effectively creates a parallel development track for the user-facing aspects of the product, ensuring that when the expensive, custom hardware finally arrives, the software that runs on it has already been battle-tested and validated, drastically reducing integration risk and late-stage rework.

Canary Release or Blue-Green Deployment: Which Is Safer?

For a software PM, terms like “Blue-Green” and “Canary” are standard deployment strategies. Applying them to hardware requires a radical translation, as the cost and logistics are orders of magnitude different. The question of which is “safer” depends entirely on your industry, product cost, and tolerance for risk. A Blue-Green deployment in software means running two identical production environments. In hardware, this would mean building and maintaining two completely independent production lines—a strategy so prohibitively expensive it’s reserved almost exclusively for mission-critical industries like aerospace or medical devices where failure is not an option.

For most hardware products, especially consumer electronics, the Canary release model is the far more practical and “safer” approach. A hardware canary release involves manufacturing a small, controlled batch (e.g., 1% of the production run) and releasing it to a limited, trusted group of users or a specific geographic market. This allows the team to gather real-world data on manufacturing defects, component failures, and unexpected usage patterns before committing to mass production. The risk is contained to a small number of units, and the learnings can be used to refine the manufacturing process or issue a firmware patch before a full-scale launch.

A third, even more flexible strategy is leveraging Feature Flagging directly in the hardware design. This involves designing the hardware to support multiple configurations that can be enabled or disabled via firmware. You can ship a single hardware SKU to all customers but enable a new, premium feature for only a small subset of them. This is the lowest-risk approach, as it requires no separate production batches and allows for instant rollback if an issue is discovered. As Agile expert Joe Justice notes, this iterative mindset is key: “R&D shops consistently produce quality prototypes up to eight times faster with Scrum for Hardware. Plus, working on an iterative Sprint cadence allows them to integrate their incremental hardware releases with a regular flow of software.”

This table from a comparative analysis of hardware development breaks down the trade-offs:

| Strategy | Implementation | Cost Level | Risk Level | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blue-Green Hardware | Two independent production lines | Prohibitively expensive | Lowest risk | Mission-critical industries (aerospace, medical) |

| Canary Release | Small controlled batch testing (1% of units) | Moderate | Controlled risk | Consumer electronics |

| Feature Flagging | Hardware designed for multiple configurations | Low to moderate | Low risk | Products with optional premium features |

Key takeaways

- Deconstruct before you build: Analyze every product through the lens of its “layers of changeability” to identify where agility is possible and where it’s not.

- Redefine “Done”: Shift the goal of a sprint from producing a shippable feature to producing a “Knowledge Asset”—validated learning that de-risks the project.

- Distribute ownership: Break down monolithic budget control. Align financial responsibility with the specific decision-making scope of each role (Product, Engineering, Project Management).

How to Implement Rapid DevOps Cycles Without Crashing Production?

The holy grail of Agile is the rapid feedback loop of DevOps: code, build, test, deploy. In hardware, the “build” and “test” phases can take weeks and cost thousands, seemingly breaking the entire model. The key to implementing rapid cycles is to virtualize as much of the physical world as possible through a robust “Digital Twin” and a “Shift-Left” testing strategy. You don’t crash production if you’ve already crashed it a thousand times in a simulation.

This means establishing an automated pipeline where engineering commits trigger virtual tests. When an electrical engineer commits a schematic change, it should automatically trigger a SPICE simulation to check circuit behavior. When a mechanical engineer commits a CAD file, it should trigger an automated thermal and stress analysis. This is “Shift-Left” testing for hardware: finding and fixing problems at the earliest, cheapest possible stage. The next step is Hardware-in-the-Loop (HIL) testing, where you run the real production firmware on a real processor, but all its inputs and outputs are connected to a simulation that mimics the real world. This allows you to test the brain of your product without needing the entire body.

This isn’t science fiction; it’s how the most complex machines in the world are built. Saab Aerospace famously used Scrum and advanced simulation to design the JAS 39 Gripen E fighter jet. By empowering teams and heavily relying on virtual validation, they produced an aircraft with superior performance at roughly half the initial cost of its competitors. As one report on the project highlights, they achieved operating costs that are a fraction of the F-35’s by reducing bureaucracy and enabling rapid, data-driven decisions at the lowest levels. They proved that with the right mindset and tools, even the most mission-critical hardware can be developed with speed and agility.

Your journey to adapting Scrum for hardware begins with this paradigm shift. Stop fighting physics and start translating principles. The first step is to sit down with your team and map out your product’s “layers of changeability.” By identifying the high-cost, immutable elements and separating them from the low-cost, flexible ones, you can begin to build a truly agile process that delivers physical products with the speed and flexibility you once thought was only possible with software.